Media in the middle

The democratic role played by the media during the failed coup attempt in Turkey did not stop censorship

19.07.2016

Journalists and their newsrooms were center stage on Friday night as factions within the Turkish military attempted a coup, leaving 265 dead, thousands wounded and the parliament building scarred from bombing. As tanks rolled onto the streets of Istanbul and Ankara, coup-plotters announced their action live from the studios of TRT, a state-run T.V. channel—by forcing anchor Tijen Karas to read their statement at gunpoint.

In response, President Erdogan gave a hastily-arranged interview on CNN Turk, appearing via FaceTime on a reporter’s phone held up to the camera. Though the improvised image seemed to show his vulnerability, Erdogan’s call for Turks to flood the streets mustered significant popular resistance to the coup on the ground.

Several hours later, the newsrooms of CNN Turk and Hurriyet, both housed within the Dogan Media Group in Istanbul, were also raided by rebelling soldiers—for the second time, a live broadcast was forcefully interrupted, and the CNN Turk cameras eventually pointed at an eerily empty studio:

At Hurriyet, soldiers held security guards at gunpoint and, as one reporter put it, “mass-arrested” the newsroom:

After police forces intervened, staff and reporters eventually left the Dogan building unharmed—but across town a photographer for Yeni Safak, Mustafa Cambaz, was shot and killed in the clashes between soldiers and police.

Social media also allowed these images—the President’s statement, the raids on newsrooms, journalists standing up to soldiers, the throngs of civilians standing up to tanks—to be rapidly proliferated, undermining efforts by rebelling soldiers to control the information released to the public. Opposition parties such as the HDP expressed their resistance to the coup on social media, emphasizing a unilateral political front against a military junta.

But four days after the quashed coup, the government’s crackdown against its plotters has rounded on the media.

On Tuesday, the state’s Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTUK) revoked the broadcast licenses of more than two dozen television and radio stations believed to be connected to the Gulen movement. Newspapers connected to the Pennsylvania-based cleric have also been targeted, as printers have refused to press their issues, and Yarina Bakis announced it will cancel its print edition.

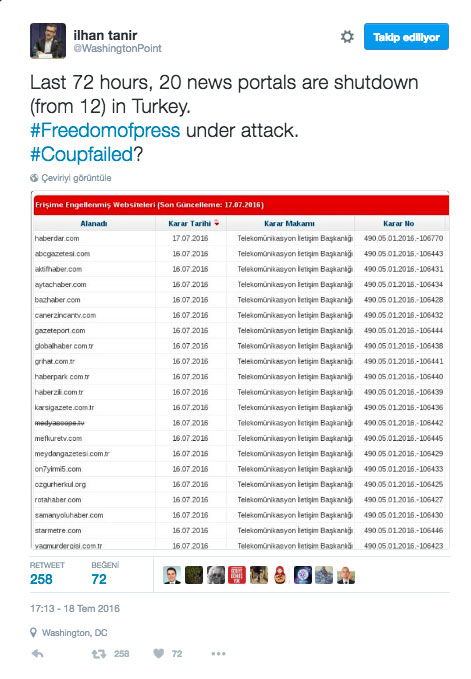

While social media remained largely unrestricted, by Sunday access to least 20 news sites was blocked by the government’s Telecommunication Authority. Haberdar and Medyascope, both restricted over the weekend, have been re-opened following appeals. (Medyascope was the 2016 recipient of the International Press Institute’s “Free Media Pioneer” award.) But many more sites, including ABC Gazetesi and Global Haber, are still unresponsive. (See the list below.)

After thousands of suspected coup-plotters were arrested over the weekend, the media seems to be next in line—early on Monday the house of Arzu Yildiz, Ankara correspondent for Haberdar, was raided early this morning after a warrant was issued for her arrest. (Yildiz wasn’t home at the time.) Unconfirmed lists of journalists in the government’s sights also began to circulate on social media, leading to speculation that more warrants will soon come.

“We are concerned that the government is using the coup to purge dissident and critical voices,” said Ben Hicks, Executive Director of the Guardian Foundation, in a statement to the press freedom organization Article 19. “Rumours of forthcoming arrests of independent journalists and other dissidents have a chilling effect on freedom of expression. The government must reassure the public that these are false rumours and actively encourage full public debate on the current situation”

At a meeting of the European Council on Monday, international diplomats also expressed worry as the scope of the government’s post-coup crackdown widened to include judges, prosecutors and journalists.

“The level of vigilance and scrutiny is obviously going to be significant in the days ahead,” John Kerry told reporters in Brussels. “Hopefully we can work in a constructive way that prevents a backsliding.”

The increased pressure on Turkey’s media comes as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) awarded its annual International Press Freedom Award to Can Dundar of Cumhuriyet, who was recently sentenced to more than five years in prison.