Embracing pesticide-free agriculture: Van cultivates sustainable solutions

Researchers at Van’s public university in eastern Turkey are leading the charge in developing organic and biological substitutes for chemical pesticides. Their work leverages natural processes to enhance efficiency while firmly protecting ecosystems, paving the way for a sustainable future in farming

12.03.2025

For centuries, Van has thrived as a center for agriculture and livestock. Its bountiful nature and favorable climate nurtured fertile lands around Lake Van and expansive plains that underpin traditional farming and herding, the lifeblood of the local economy. In recent years, the region has ascended as one of Turkey’s premier hubs of sustainable agriculture, seamlessly transitioning from conventional practices to innovative, eco-friendly methods.

At the forefront of this transformation is the Department of Plant Protection at Van Yüzüncü Yıl University (YYÜ). Here, researchers are pioneering alternative strategies that foster robust plant growth while preserving the environment. Harnessing state-of-the-art climatic chambers and laboratories, the faculty underscores the feasibility of significantly reducing chemical inputs in agriculture — a testament to the extensive, diverse body of work that continues to evolve.

Central to these endeavors is the development of environmentally sound techniques to shield crops from myriad threats, offering a viable substitute for traditional chemical treatments. Among the promising approaches, scientists are investigating the deployment of living organisms to curtail the spread of plant diseases, employing beneficial bacteria to manage pest populations, and leveraging organic fertilizers that not only nourish plants but also help mitigate insect infestations.

Professor Demir and her team have developed a novel fertilizer that combines whey with a microorganism that thrives on plant roots.

Professor Semra Demir, head of the department and a distinguished phytopathologist, explains, “The most effective alternatives to reducing pesticide use lie in biological control and harnessing the positive impact of food and agricultural waste. When these wastes are properly utilized, they bolster plant development and resilience.” Her groundbreaking research on fungi —an essential kingdom that includes mushrooms— has been instrumental in shaping these natural agricultural solutions.

Fungi, commonly known as mushrooms, play a vital role as a natural fertilizer. Photo courtesy of Van Yüzüncü Yıl University researchers.

Over 25 years, YYÜ has amassed a wealth of knowledge in eco-friendly practices that serve as viable alternatives to chemical use. Their research delineates two primary categories: one employs naturally occurring organisms to combat plant diseases, while the other utilizes predatory insects or bacteria to control pest populations. These biological control methods, complemented by studies on leveraging innate plant mechanisms to suppress weeds, pave the way for a future in which agriculture thrives in harmony with nature.

Innovative approaches in farming: Fungi and whey

Professor Demir graciously escorted me on a tour of her department’s campus, beginning with a visit to the laboratory. The Department of Plant Protection is divided into two specialized sub-departments: entomology, which delves into the study of insects, and phytopathology, dedicated to understanding plant diseases. Both the laboratories and the climate-controlled research rooms are abuzz with numerous innovative studies. With more than 30 years of research experience, Professor Demir has published extensively in esteemed academic journals, and her office is adorned with plaques that celebrate her many accomplishments. Her genuine passion and commitment to her work are truly contagious, and it is evident that she is held in high regard by her students.

Currently, Professor Demir and her team are developing an innovative “microbial fertilizer.” In development for nearly 25 years, this sophisticated product combines 13 distinct microorganisms to harness the beneficial properties of fungi, thereby promoting plant growth and reducing the dependency on chemical fertilizers.

Professor Demir explains that these fungi are especially beneficial for low-fertility soils — areas that are saline, arid, contaminated with heavy metals, or even classified as desert lands. They excel in conditions of “plant stress,” making them applicable not only around Van but also in diverse regions with varying climatic conditions. Her team has achieved promising results through trials on a variety of annual crops, including vegetables such as tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, and potatoes; cereal grains like wheat and maize; and legumes such as lentils, chickpeas, and beans.

The research commences with the university’s agricultural lands and extends to agricultural regions in multiple provinces. Photo courtesy of Van Yüzüncü Yıl University researchers.

In parallel, researchers at the university are optimistic about their pioneering study on utilizing whey as an agricultural fertilizer. Their research demonstrates that applying whey —either on its own or in tandem with beneficial microorganisms— can significantly enhance plant growth. While only a few factories in Turkey currently produce whey powder, this often-discarded liquid by-product of cheese-making poses environmental risks when improperly disposed of. Addressing this challenge, Professor Demir and her team have developed a novel fertilizer that combines whey with a microorganism that thrives on plant roots —a project supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK).

“In Europe, nations like Germany, and France implement quota systems where farmers receive guidance and purchase guarantees from their respective organizations.”

Reflecting on the innovative nature of their work, Professor Demir remarked, “We worked on a model which might be the first of its kind in the world. There was no similar study in the scientific literature.” She added, “We obtained very good results when we used the fertilizer in trials with many crops including peppers and eggplants. There is a handful of farmers in Adana, Tokat, Antalya, Diyarbakır, Konya, and Aksaray we work with and advise, and we have received excellent feedback from them.”

High yield pressure caused by economic instability biggest short-term challenge

Are these methods truly well-known and widely embraced? Why do so few producers adopt them? Professor Demir explains that the initial investment required to shift from conventional, pesticide-dependent agriculture to these innovative alternatives can be prohibitively high, deterring many from committing to long-term change. “Producers typically seek immediate returns, and while alternative methods are both environmentally sound and effective, their benefits materialize over the medium to long term,” she notes. Market pressures further compound the issue. “As a result, demand for these alternatives remains insufficient, and producers continue to rely heavily on pesticides — even though the seemingly low short-term costs can inflict severe long-term damage on both the environment and human health.” Addressing these producer concerns, she emphasizes, is crucial for broader adoption.

Professor Semra Demir.

Each year, a substantial quantity of Turkey’s agricultural exports is rejected due to excessive chemical residues. When even basic products fail to meet international standards, they often remain confined to domestic consumption, leading not only to economic losses but also to risks to public health and nutrition. Confronted with the harmful impacts of chemical use, how can farmers be encouraged to adopt more sustainable practices? To explore this pressing question, I visited the Van Metropolitan Municipality.

Gülşen Güven Yördem, an expert agricultural engineer with nearly a decade of experience at the Department of Agricultural Services of the Van Metropolitan Municipality, works directly with farmers, offering keen insights into the challenges they face. Yördem stresses that the reliance on chemicals in agriculture is not solely a matter of individual choice but is also driven by structural factors — such as insufficient education, economic insecurity, and inadequate oversight. “Farmers often resort to chemical pesticides to achieve immediate gains rather than waiting for the more gradual benefits of sustainable practices,” she explains. She believes it is unjust to place the entire burden on farmers, noting, “Many are not well-informed about alternative methods and instead rely on the advice of employees at fertilizer supply companies, which are often poorly regulated.”

Their findings indicate that these organic solutions bolster plant resilience by enhancing innate defense mechanisms, all while ensuring no adverse effects on human health or the environment.

Furthermore, farmers’ struggle to secure adequate profits compels them to use more fertilizers in pursuit of higher yields — a trend exacerbated by economic instability and a lack of robust support systems. Yördem points out that ineffective agricultural policy planning only deepens this cycle. “In Europe, nations like the Netherlands, Germany, and France implement quota systems where farmers receive guidance and purchase guarantees from their respective organizations,” she remarks. Establishing a similar protective and educational framework in Turkey, she insists, is essential to promote sustainable agriculture while safeguarding the livelihoods of its farmers.

From climatic chambers and academic journals to the dinner table

A major study at Van University’s Plant Protection Department is pioneering environmentally friendly solutions to combat diseases affecting walnut trees. This international endeavor, carried out in bilateral collaboration with Hungary and supported by TÜBİTAK, is led by Professor Younes Rezaee Danesh, with significant contributions from specialists in the phytopathology department.

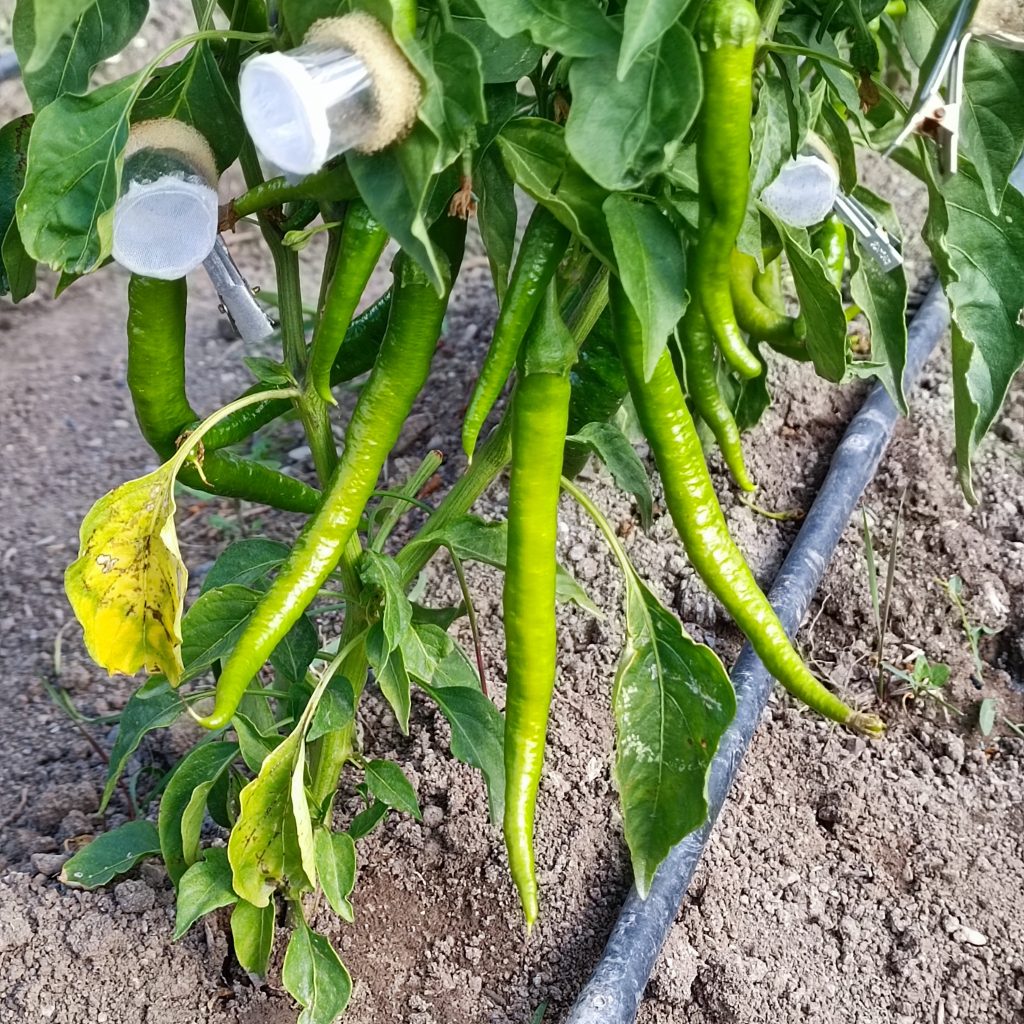

Green chili pepper plants that were treated with microbial fertilizers.

I then met with Associate Professor Evin Polat Akköprü, also of the Plant Protection Department. An entomologist since 2022 and an accomplished musician who regularly graces classical Turkish music events, Professor Akköprü and her team are exploring innovative alternatives to chemical pesticides. They are investigating the use of bacteria and insects to enhance plants’ natural defense mechanisms. “The bacteria we utilize are inherently biological,” she explains. “Our studies demonstrate that protecting plants from harmful insects without chemicals is not only environmentally sustainable but also economically viable for farmers.”

The university’s climatic chambers have established it as a key player in Turkey’s sustainable food and agriculture landscape. Photo courtesy of Van Yüzüncü Yıl University researchers.

Professor Akköprü recounted a comparative study on the use of vermicompost —a fertilizer produced by earthworms— for pepper cultivation. Traditionally, chemical pesticides are used to control insect infestations on pepper plants. However, her team’s open-field trials revealed that vermicompost delivered comparable results. This naturally leads to a fundamental question: Why choose chemicals when a proven, natural alternative is available?

Associate Professor Evin Polat Akköprü.

Currently in its third year, her team is also assessing the efficacy of organic fertilizers such as leonardite and biochar, combined with specific bacteria, to manage pests — particularly aphids that threaten bean and pepper crops. Their findings indicate that these organic solutions bolster plant resilience by enhancing innate defense mechanisms, all while ensuring no adverse effects on human health or the environment.

I also had the pleasure of speaking with Associate Professor Reyyan Yergin Özkan, whose research in sustainable agricultural ecosystems is equally compelling. Her work harnesses natural processes like allelopathy, a phenomenon where plants release chemicals to either inhibit or promote the growth of neighboring vegetation. A classic example is the walnut tree’s effect on its surroundings, encapsulated in the old adage, “Don’t sleep under a walnut tree.” Professor Özkan’s studies explore such interactions for innovative applications in weed management.

In one project, her team investigated an essence derived from post-harvest white cabbage leaves as a natural herbicide. Their research demonstrated that this extract effectively curbed the spread of red root amaranth without harming maize, thereby offering a promising alternative to chemical herbicides.

Associate Professor Reyyan Yergin Özkan.

At the department, environmentally friendly agricultural methods are initially trialed in state-of-the-art climatic chambers, where factors such as temperature, humidity, and light are rigorously controlled. Promising techniques are subsequently validated under field conditions, often through multi-year studies, and the findings are shared with the scientific community via reputable national and international journals.

These efforts are not merely academic, they are designed to transform agricultural practices. With robust support from TÜBİTAK and in collaboration with the Directorate-General of Agricultural Research and Policy (TAGEM), the department strives to increase the availability of healthy, sustainably produced food. Alongside a dedicated team of researchers, numerous students contribute each year, ensuring that these innovative, environmentally friendly practices continue to evolve and make a lasting impact on modern agriculture.

85 percent of food products contain residues from multiple pesticides

The extensive application of pesticides profoundly disrupts the natural balance of soil and contaminates vital water sources. As these chemicals infiltrate both groundwater and surface water, they inflict lasting harm on aquatic life and erode biodiversity over time. Moreover, pesticide residues in food can destabilize hormonal balance, weaken immune defenses, and increase the risk of serious illnesses, including cancer.

A leaf of a bean plant that has been treated with natural pesticide methods.

The Pesticide Atlas project estimates that around 385 million cases of pesticide poisoning occur worldwide each year, leading to approximately 11,000 deaths directly attributable to such exposure.

A 2019 study by Greenpeace Mediterranean in Turkey revealed that 49 percent of randomly sampled foods contained pesticide residues — substances that are particularly detrimental to aquatic organisms, bees, algae, and other beneficial insects. Furthermore, 42 percent of these samples harbored pesticides known to bioaccumulate in wildlife, resulting in persistent toxic effects.

Similarly, research conducted by the Center for Food Studies at Akdeniz University detected pesticide residues in 85 percent of the food samples analyzed.

This article was published as part of a program supported by the UK Ankara Embassy’s Bilateral Cooperation Programme. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of P24. The UK Embassy cannot be held liable for the information provided in this article.