Exchanging curtains under the state of emergency

On my way to the shopping center, I found myself in custody; just an ordinary day in Turkey’s ongoing emergency rule

29.08.2016

The return period for a pair of curtains that I bought a few weeks ago was about to expire. On Sunday evening, at around 7 p.m., I went out of my house in the Gayrettepe neighborhood and headed towards the nearby Cevahir Shopping Mall. I was going to return the drapes that I bought earlier and pick new ones and in the meantime take an evening walk.

The Gayrettepe Public Security Branch Directorate was on my way. Right next to the directorate building I saw people waiting for their relatives who are in custody. Only three weeks ago, I was at that very spot, waiting for my colleague, the journalist Bülent Mumay, and later for my professor, the poet Hilmi Yavuz. This place has almost turned into a permanent station of suffering with the only change being those who stand in wait. That Sunday evening, among those holding vigil, were mothers with their babies and elderly people. Some of them had brought with them folding picnic chairs. They were all desperately hoping to hear a piece of news from inside the Public Security Directorate. Thinking I might Tweet about it or perhaps use it with an article later on, I snapped two photos of the crowd and walked away. I had a pair of curtains to change.

A while later I was stopped by a man who ran after me. He told me he was a police officer. He asked to see my ID and I showed him. He then asked me why I took the pictures. I replied: “I’m a journalist. I wanted to take those people’s photos after seeing their situation.” He said, “Well, what if there’s going to be an attack on the directorate and you’re surveying [for a terrorist organization].” I told him that I only focused my camera on the people who were waiting there and that there was no way the building could even fit in the picture. The Gayrettepe Public Security Branch Directorate has already been photographed a million times before by various journalists anyway. Without even looking at the pictures that I took, he told me to “go with” him. When he wanted to seize my cellphone, I said, “I can only give it to you if you keep a written record.”

And thus all of a sudden I found myself inside the Public Security Branch. Then they started investigating me while in the meantime having “small talk” with me. I didn’t look like a bomber or anything but I guess I wasn’t too favorable a journalist for them either. Among the questions I was asked were “Do you write about the schools that are being shut down?” and “Did you work for the Taraf daily before?” They held me for hours without even starting a formal procedure. In case anything happened to me there, there was no official record, nor did anyone know that I was being held.

When I told them, “You cannot keep me in custody without papers,” the police officer slammed the door, banged a real hard fist on the table, and said: “This is emergency rule, we can hold you until morning without any records if we want to, we can do anything, you can complain whenever you’re free.” Since they hadn’t started any paperwork, I wasn’t entitled to the right to call a relative. The police officer told me something along the lines of: “If you’re that considerate of your relatives, don’t take photos in the middle of the street. I for instance care about my relatives and when something [a scuffle or some other incident] happens near me I don’t even look to see what’s happening.” The shopping center had already closed and I was feeling like I was about to be thrown into a bottomless well.

Then they told me, “Somebody is looking for you” and the course of events started to take a different turn.

Luckily, when the police officer first told me to “go with” him, I had called my friend, the lawyer Veysel Ok, from the independent journalism platform P24, on my cellphone. When Veysel called me back he couldn’t reach me and so he was worried and he called the Gayrettepe Public Security Branch only to be told that they had no records with the name of Tuğba Tekerek. He didn’t trust them and so he came over to the directorate to check in person. I was very lucky. Somebody out there knew I was being held and as of that minute, it wasn’t going to be that easy for the police to do whatever they pleased.

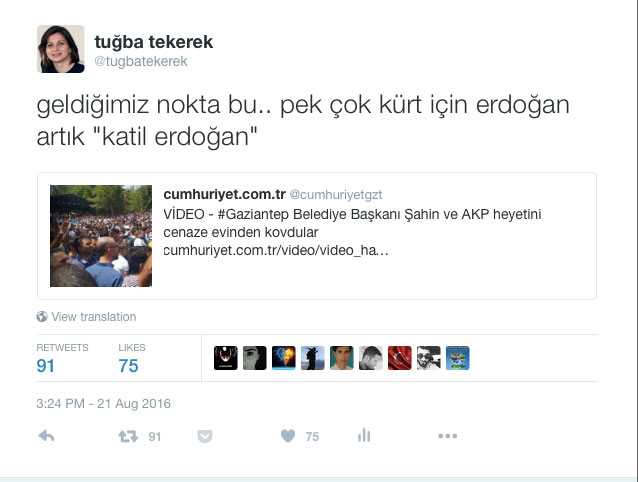

For some strange reason the police officers could only reach the prosecutor only after my lawyer showed up! They took my testimony and then let me call a relative . In the meantime, thanks to their amazing (!) intelligence work they had discovered my latest Tweet and have decided to charge me with “insulting the president.” The photos that were the reason for my being taken into custody in the first place have now been forgotten. Whereas in my Tweet I had quoted a Tweet with a video, originally posted by the Cumhuriyet daily. In that video, a large group of Kurdish people were chanting “Murderer Erdoğan” in protest of Ak Party (Justice and Development Party) deputies who attended a funeral ceremony following a recent deadly attack by ISIL in Gaziantep. My Tweet was reporting about that situation: “This is the point we’ve come to. For many Kurds, Erdoğan is now ‘Murderer Erdoğan’.”

Only one Tweet was enough reason to be taken into custody. And I was headed to the detention cell.

Inside the detention cell with court reporters

As I was wondering whether I was going to be alone in the detention cell or share the room with another person, the gate opened and I was met by the sight of dozens of shoes. And odor. Inside the three detention cells that could normally accommodate a maximum of three to five people, there were 27 people in total. People were lying on the floor, with their knees pulled up, because there was simply not enough room for one to sit or lay on the floor with their legs stretched. Later I found out that only a few days ago there were 43 of them and some of them even had to sleep on the corridor.

When I joined the others in detention it was a little past 3 o’clock in the morning. My detention cell mates asked me if I was a stenographer as well. As I was trying to figure out what that meant, they explained: “We’re court reporters.” “… We all used to work at the Anadolu Courthouse.” Twenty-four out of the 27 were stenographers. They each had the job because they had successfully passed a test where they were required to type a minimum of 90 words in three minutes, and now they were in confinement for being members of “FETÖ” (“Fethullahist Terrorist Organization”).

At such a late hour, half asleep, they all surrounded me, hoping to find out about what was going on outside in the world; they were hungry for even one tiny piece of news. They had been there for seven days now. They were denied visitation, they didn’t have lawyers, and criminal defense lawyers appointed by the state didn’t want to defend them. (According to what they told me, police officers from other units in addition to the anti-terror unit were involved in “FETÖ” operations. When the police told the court-appointed lawyers they were assigned a homicide case, they accepted the job, thinking they’d defend a murder suspect. When they were told the anti-terror department was calling, the lawyers knew it would be a “FETÖ” case and refused to take up the cases.)

When I told them I was in custody because I took photos near the Public Security Branch Directorate, the look on their faces was indescribable; I had photographed the very same people these women were yearning to hear from — their relatives. Then they started showering me with so many questions, “Have you seen such and such a kid?” “Was there a woman among them who liked like such and such?” They were all between the ages of 25 and 30 and most of them had children. One of them had a seven-month-old baby, carried twice a day to the detention facility by the woman’s relatives to be breastfed, all the way from Sultanbeyli, which is a two-hour drive from where we were. She was the luckiest among them all, because the others, even if their kids were only 15-months-old, weren’t allowed to see them. Every time the seven-month-old was brought to his mother some of the other detainees had nothing else to do but cry silently in one corner. They were either thinking of their own kids, or thinking, “My mom must be missing me.”

There was also an eight-month pregnant woman who didn’t take part much in the conversation, but was rather busy dealing with her uncomfortably big belly, with her discomfort written all over her face. She said that in addition to working as a court reporter she was also studying law — a field she now hates. When the police operation began she was on maternity leave. When she found out that a search warrant had been issued for her, she told the prosecutor with whom she worked that she wanted to surrender. She also has a 3-and-a half-year-old daughter. “I have almost forgotten her face, I wish I had brought with me a picture of her,” she said with a sob. Another woman replied: “They wouldn’t let you. There’s not even a mirror in here!” Yes, this was a place where one could even forget how one’s own face looked like.

The fluorescent lamp on the ceiling was switched on all the time, even during daytime. And since our watches had also been confiscated, there was no way of telling what time of the day it was. One could only see the sunlight percolating through a 10 centimeter-wide opening of a window behind another window that reflected on the wall across. The detainees were allowed to the courtyard for fresh air on an arbitrary basis, for arbitrary periods of time. For example, the day before, they were given five minutes in the courtyard around 5 o’clock in the evening. The same rule of arbitrariness also applied in one’s access to a toothbrush. We were feeling as though we were stuck inside the engine of an air conditioner that doesn’t do any good other than making a horrible noise. I was trying not to think about the hot air surrounding my body and how difficult it was to breathe. We had no idea how long this was going to last.

When they asked me if there was “any reaction outside to our arrest,” I couldn’t say anything. Then one of them responded: “What were we saying back when other people were getting arrested? We used to just say, ‘Too bad, hopefully those who aren’t guilty will be released.’ So that’s probably just what people are saying about us now.” One of them was telling me about how she tried to get a credit card back in 2014: “[No other bank but] only Bank Asya gave me a credit card. That’s the only crime I committed.” Another one was suspecting that she was being held on account of her brief time some seven years ago answering phones at a preparatory course run by the Gülen movement. Yet another was asking, “I’ve never been to their preparatory courses, taken a loan from Bank Asya, been to one of their meetings, read Zaman [newspaper]. Why on earth am I here?”

The intention was to wear these people out and get them to “tell” things. The police officers had told them that almost all of the nearly 20 court reporters who had been referred to the prosecutor’s office before them were arrested. But after my release from custody I found out that almost all of those people had actually been released. Not only were these people being deprived of information, they were deliberately being misinformed.

The next morning, around 11 a.m., a police officer announced my name. I left the premises with a feeling of guilt that still haunts me. I knew that P24, the Ben Gazeteciyim (I Am a Journalist) Initiative, independent media outlets that are too few in this country these days, all stood up for me. If it weren’t for them, I couldn’t have survived being confined in some place in the middle of nowhere. But for the people I saw there, it was far more difficult.

The courthouse as a journalist grinding machine

Once I left the detention cell, I was first taken to medical examination (just like when I was detained, the physician examined me in the presence of a police officer, despite what the law says. It wasn’t a full examination either — I was simply asked if I was subjected to “battery” during the detention period). When we arrived at the Çağlayan Courthouse my lawyer Veysel Ok was already there. We were then taken to the office of the prosecutor. The prosecutor picked my file from among a pile stacked upon his desk and took a quick look. Without asking me anything, he started writing down something. Veysel and I looked at each other. Considering the fact that I got detained on my way to shop for curtains, I could as well get arrested. “What are you writing?” I asked anxiously. He said, “You’re free, you’re free.” In the meantime I was now facing investigation with the charge of “insulting the president” but we could think about that later. Right after I went out of the prosecutor’s room, [the journalist] Fehmi Koru went in. Next up following Koru were Özgür Gündem editor in chief Zana Kaya and managing editor İnan Kızılkaya. I don’t know anything about the file regarding Koru, but İnan and Zana have been arrested. Just like Veysel said, the Çağlayan Courthouse was working like a “journalist grinding machine.”

As to the curtains, eventually I did change them — despite a lot of people advising against it, or telling me to at least take a different route to the shopping mall. And despite my fears, I still took the same route. Furthermore, this time I had news for the relatives of people with whom I shared the same fate for one night. Last night marked the 10th day of their confinement, and almost all of them were still waiting to be interrogated.

P.s: There is one proven fact that this experience has taught me: Solidarity is extremely important. I would like to take this opportunity to thank P24, Yasemin Çongar, Veysel Ok, Fatih Polat, and my friends at the Ben Gazeteciyim Initiative, and everyone else who stood up for me and voiced my situation publicly.

This blog was originally posted in Turkish on Aug. 26, 2016. English translation by Yasemin Gürkan.