My columnist job “stolen” twice in four months

But the ramifications of this latest attack on Turkish press are much more important than my personal loss…

06.03.2016

Losing one’s job is part of corporate life. But what if you are to lose your job not because you are bad at it, or because there isn’t a good fit, or because your company needs to downsize, but simply because the government does not want you or your firm? I am unfortunate enough to have experienced that twice during the last four months.

Analyzing preliminary election results right after the Nov. 1 Turkish general election, Swedish economist Erik Meyersson noticed several statistical anomalies. For example, the distributions of the last digits in the ballot box votes of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) were very different from the Jun. 7 general elections. He concluded that “this analysis shows evidence that would be consistent with widespread voting manipulation, not proof of it.”

I found his results important and interesting enough to feature in my semi-weekly Hürriyet Daily News (HDN) column on the Turkish economy (and politics with an economics twist). However, HDN’s Editor-in-Chief Murat Yetkin disagreed. When he refused to print my column, I took it to the Independent. I was then summarily fired, even though I had no exclusivity agreement with HDN and was regularly publishing my regular or censored columns elsewhere, for “publishing a column I knew to be against HDN's editorial policy in another newspaper as an HDN columnist,” becoming yet another Turkish press casualty.

To be honest, I didn’t expect to stick around for much longer, especially after the obvious change of tone in the paper from critical to submissive after the AKP’s election victory. Pressure on HDN had considerably increased in the last couple of years. I was told that “people from Ankara” were calling the paper to name columnists supposedly insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. I was getting censored once every few weeks, for example for comparing the cost of Adolf Hitler’s Reich Chancellery to Erdoğan’s Ak Palace – or even for suggesting that the government could come after the Koç Group for their decision to shelter gassed Gezi protesters at their Divan Hotel in Taksim. However, I did not expect to get sacked so soon, and for such an “innocent” column.

After some soul-searching, I knew I had to continue writing and knocked on the door of Today’s Zaman (TZ), an English-language daily associated with the Gülen movement, even though several friends had advised against it: The pragmatic Machiavellians had warned me that people were trying to disassociate themselves from the Gülenists – while the ideologues felt the need to remind me the injustices handed out by them during the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials. Both actually strengthened my resolve to write in TZ. After all, I have always believed that two wrongs do not cancel out, and even those who have practiced injustice deserve justice.

I started at TZ more or less where I had left off at HDN: Another study, this time by several American political scientists, had recently found irregularities in many ballot boxes in Turkey, using methodologies similar to Meyersson’s. So my first TZ column was about that paper as well as Meyersson’s results. But alas, my stint at TZ was not meant to be long. A day after my second column on Turkey’s dismal environmental record was published, the government took over Zaman and Today’s Zaman. A colleague who was at the paper at the time told me that “the police were extremely fierce, as if they were specially instructed to be so.”

And so here I am without a home for my columns for the second time in four months. But the ramifications of this latest attack on Turkish press for the country are much more important than my personal struggle. For one thing, Turkey’s place as one of the countries with the least freedom of press has ben sealed for good. The country’s press is already defined as “not free” by Freedom House, and ranked 149th in the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index. The latter was prepared before the Gülenist media takeovers as well the arrests of daily Cumhuriyet’s editor-in-chief Can Dündar and Ankara correspondent Erdem Gül. We shall probably see an even further drop in the rankings in 2016.

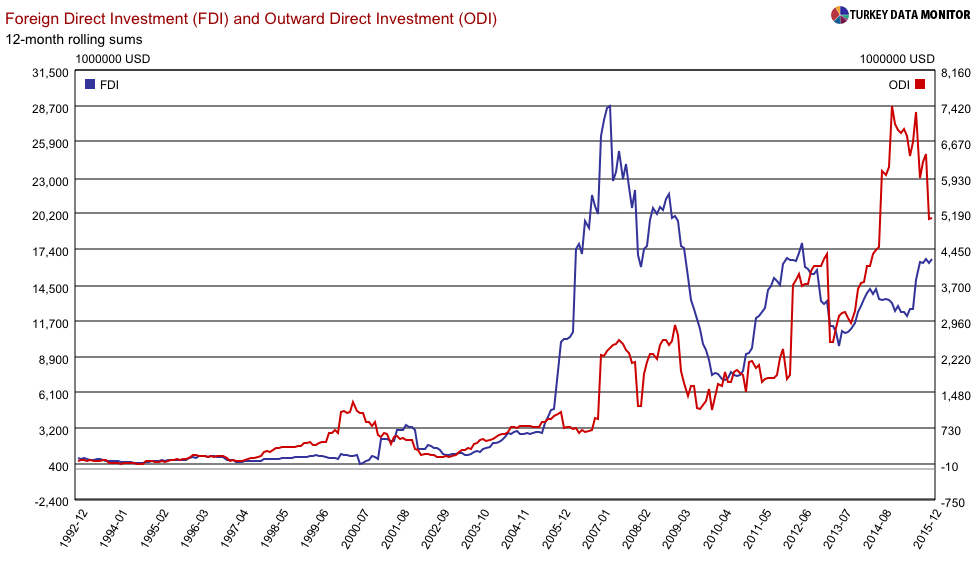

There are also economic consequences. Wouldn’t any foreign multinational think twice before investing in Turkey if they see that discretion rules supreme over the rule of law, that the government can seize any company whenever it wants? It is then no surprise that despite a several recent one-off, big-ticket items, foreign direct investment (FDI) into the country is far from its highs almost a decade ago.

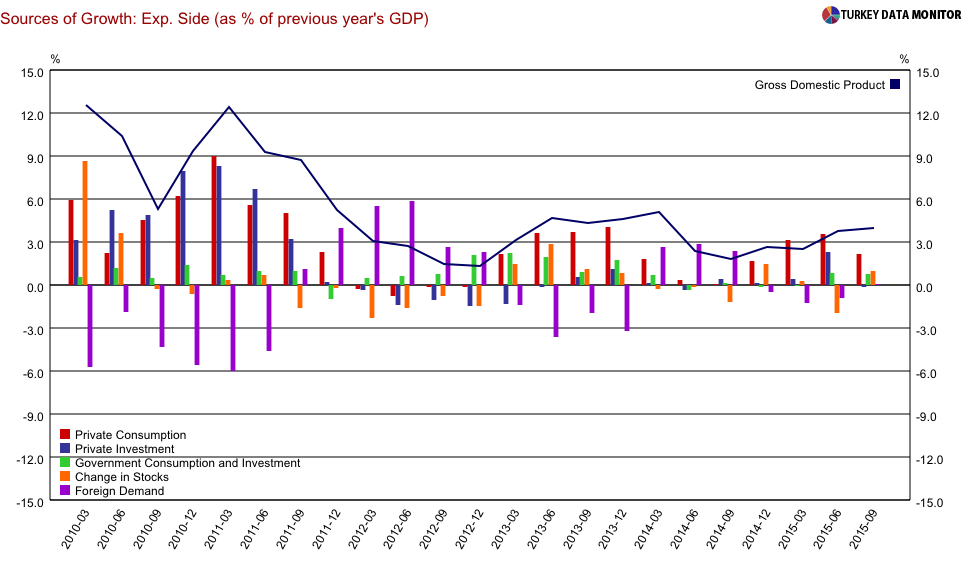

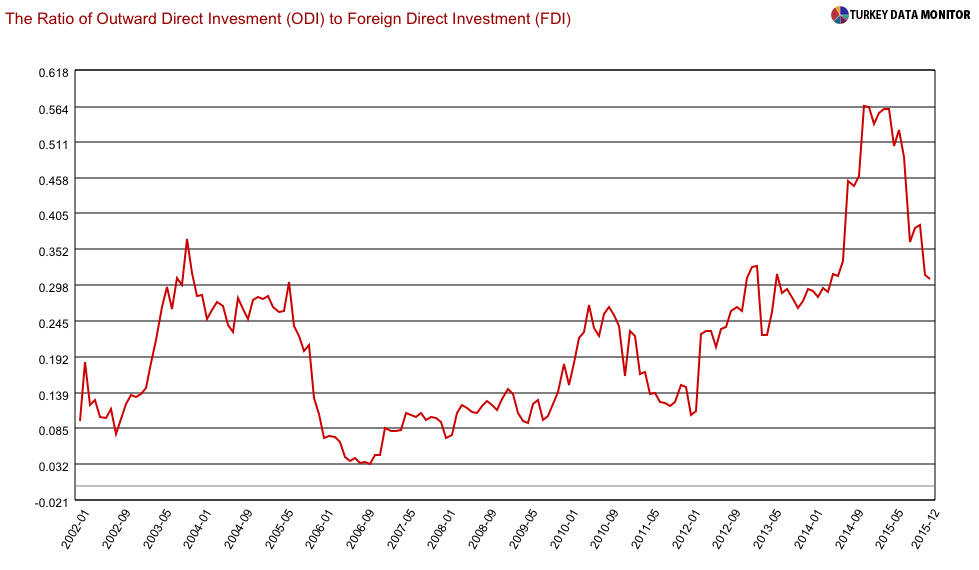

And it is not just foreigners who are having thoughts on investing in the country. Private investment has contributed more than one percentage point to growth only twice during the past four years. In fact, Turkish businessmen who have the means and knowhow to invest abroad are increasingly doing so. While FDI has hit rock-bottom, outward direct investment (ODI) has shot up. As a result, the ratio of ODI to FDI, despite a recent plunge that will probably prove to be temporary, is still very high.

Seasoned economy journalist Kerim Karakaya wrote in his blog recently that “our profession has been stolen from us.” Left without a home for my columns twice in the last four months, first indirectly then directly as a result of government intervention, that’s exactly how I feel. But it hurts much more to see Turkey’s democracy and economic future thrown down the drain.