The ‘mellow’ Marmaris salamander seeks to break free from Red List

The endemic salamander of Marmaris is facing extinction. Rescuing this serene and gentle creature from the Red List requires safeguarding its habitat against the dual challenges of construction frenzy and climate change

25.03.2025

Our all‐terrain vehicle shudders along the rugged road near Muğla. After passing the mesmerizing Aegean landmark of Gökova, a sign pointing to the ancient city of Thera appears on the right. The sun gleams in a deep blue sky, casting a warm, inviting glow. Yet, despite the beauty of this winter day, the conditions are less than ideal for spotting the elusive Marmaris salamander, a creature that favors rainy weather and retreats underground during summer to escape the heat. In a fleeting moment of doubt, I muse, “We’re defeated from the start,” but the encouraging words of the Muğla Nature Conservation and National Parks officers soon dispel my doubts.

Reaching the farthest point accessible by vehicle, we step into the forest with the intent of uncovering traces of the Marmaris salamander. We begin by carefully lifting the large stones scattered along our path. It isn’t long before a small creature darts swiftly from beneath one such stone. Convinced it might be our sought-after salamander, I swiftly raise my camera. However, upon reviewing the image, I realize that the creature resembles a field lizard. Despite my diligent search, no further sign of the salamander emerges, and I leave my initial attempt feeling disheartened.

Chief Serhat Şener of Muğla Nature Conservation and National Parks then advises that we focus our search on the northern slopes of the mountains. Changing our original route from Kötekli in the north, we trust Mr. Şener’s instincts and steer eastward toward Çiçekli. Upon arrival, as we step from the vehicle, Mr. Şener directs us to a cluster of large stones, remarking, “Let’s look here first.” When we lift these stones, the elusive Marmaris salamander reveals itself, as if it had been waiting for us all along.

Given the Muğla’s vast area and its susceptibility to the impacts of global warming and rampant construction, rigorous conservation efforts are essential.

“Here,” Mr. Şener announces with a warm smile. Eagerly, I approach with my camera. Expecting a nimble creature akin to a lizard, I am instead greeted by a calm, composed animal that poses gracefully. Its relaxed demeanor endears it to me, and I affectionately dub these salamanders “mellow.” After capturing a few photographs, I gently restore the stones, leaving the enchanting, black-eyed creature undisturbed.

Our search resumes beneath several more stones when unexpected sounds catch our attention. “Is it a pig?” Arzu, a team member, inquires after hearing noises reminiscent of a distant gunshot. After a moment of attentive listening to the rustling leaves, Mr. Şener suggests that the sounds might well be turtles during their mating season, a thought that brings a smile to our faces as we resume the hunt for another salamander.

Locating Marmaris salamanders is no easy task. These creatures ‘estivate’ in summer and lead a discreet life hidden beneath stones in winter. Photo: Songül Karadeniz

It isn’t long before we locate a second specimen and photograph it. Meanwhile, Haydar Bey, whose thirty-two years at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry have endowed him with deep insights, and Mr. Şener engage in an enlightening conversation about the markings on the trees. They discuss the necessity of controlled felling for mature trees and explain the significance of the stamps on their trunks. Enriched by both nature and thoughtful discourse, we eventually embark on our journey back.

“Marmaris salamanders benefit from remaining active during winters”

Along the way, Mr. Şener shares that they are attempting to capture an image of the elusive Anatolian leopard with a photo trap. Although this majestic species was once thought to have last been seen in 1974, its most recent sighting occurred in 2023. The Nature Conservation and National Parks team is determined to demonstrate that the leopard continues to inhabit the mountains of Muğla, too.

“Salamanders primarily feed on insects, and in areas ravaged by fires, the resulting decline in insect populations can deprive them of sustenance.”

The Muğla team is comprised of staff from one directorate and six subunits, each averaging five to six members. Given the province’s vast area and its susceptibility to the impacts of global warming and rampant construction, rigorous conservation efforts are essential. Professor Eyüp Başkale, a faculty member at Pamukkale University’s Department of Biology and a dedicated researcher on the Marmaris salamander, observes that current staffing levels are insufficient for the task.

“We have consistently observed genuine commitment from the staff at both the Muğla and Marmaris Nature Conservation and National Parks branch directorates,” says Başkale. “However, due to the expansive area they must cover, and the region’s popularity as a tourist destination, the number of personnel is simply inadequate. When considering Ula and the regions of the Datça Peninsula, the Marmaris area is extensive, and nearly all of it falls within the species’ range, making effective conservation both challenging and costly.”

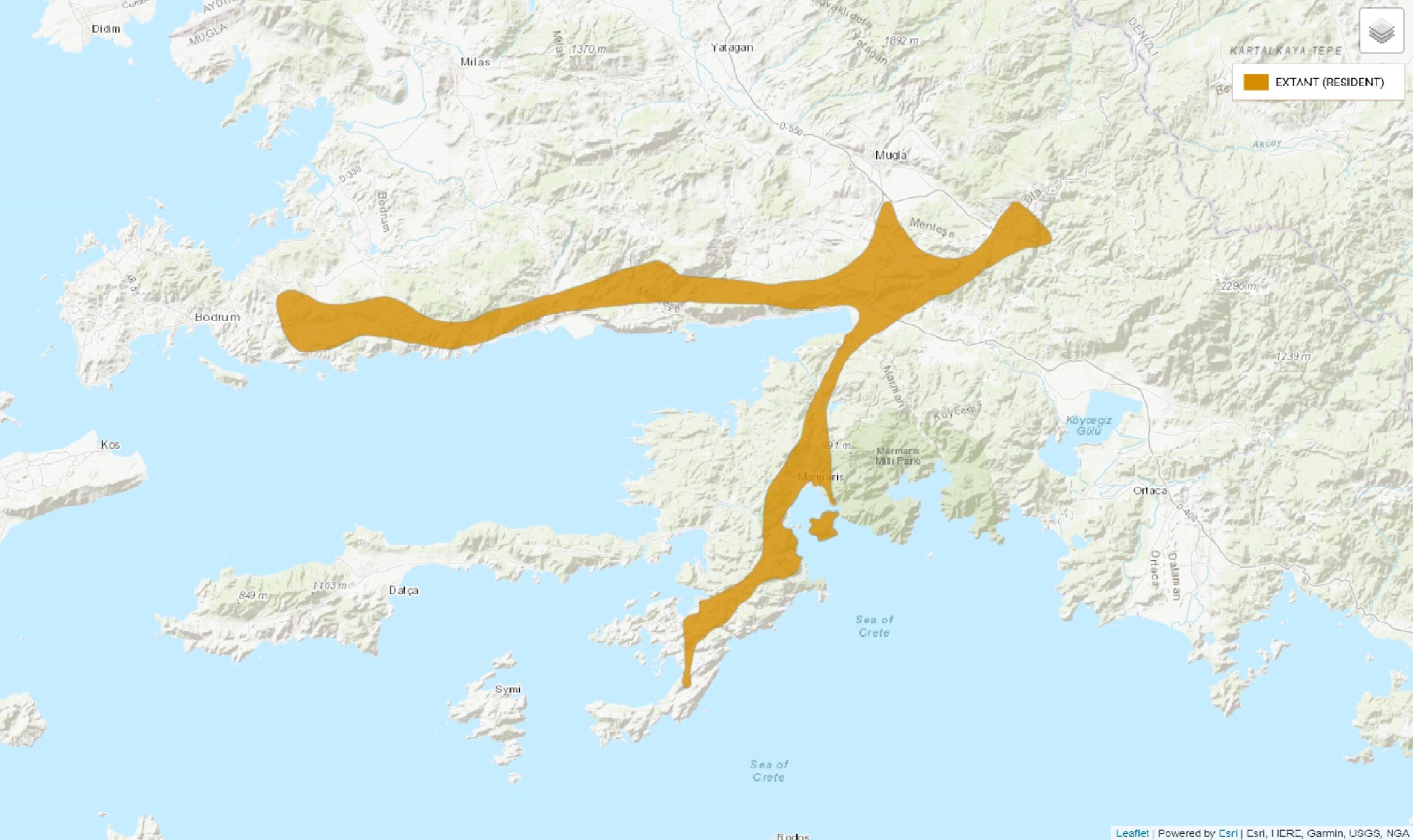

Distribution range of the Marmaris newt, as detailed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) database. Source: iucnredlist.org

The Marmaris salamander is classified as “Endangered” (EN) on the IUCN’s (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List. In response to the species’ decline, officials have partnered with scientific authorities to launch joint initiatives under a cooperative protocol.

“Conservation measures have yielded remarkable results, especially over the past five years of monitoring,” explains Başkale. “A significant contributing factor was the pandemic; the reduced human activity during quarantine lessened the risks of damage to these sensitive areas in winter, enhancing our protection efforts by approximately 80 to 90 percent.”

Human activity is just one of the many threats facing the Marmaris salamander. In the Mediterranean region, where extreme heat and frequent wildfires are increasingly common, even a modest 2-degree temperature rise can elevate the risk of forest fires by 30 percent. Başkale notes that rising temperatures can even trigger spontaneous fires.

“We have particularly observed this during the fires in the Marmaris region, where steep, inaccessible mountain ranges hinder firefighting efforts, leading to prolonged burning and more severe impacts on wildlife,” he explains. “Although the Marmaris salamander benefits from being active in winter, when forest fires are rare, the destruction of forest vegetation during fires undermines the biological conditions it requires.”

“We initiated observation studies in all known habitats of the Marmaris salamander, identifying critical areas and developing tailored plans to address emerging issues.”

The salamander’s survival hinges on very specific ecological conditions. Başkale emphasizes that both soil and air humidity are vital, as is the nutrient richness of the environment. “Salamanders primarily feed on insects, and in areas ravaged by fires, the resulting decline in insect populations can deprive them of sustenance. Furthermore, insufficient moisture compromises their hydration, potentially forcing them to migrate. While forest fires may not directly harm the Marmaris salamander, the subsequent ecological disruptions can ultimately trigger migration or even death for these delicate creatures,” he says.

An observable trend toward northward migration

Officials from Muğla Nature Conservation and National Parks informed me that the areas where the salamanders resided after the Marmaris fire were intentionally left undisturbed to allow nature to heal. They explained that monitoring studies revealed the fire had caused a “flashover” through the upper layers of the forest. In fire ecology, allowing burned areas to recover naturally is considered the least intrusive method for both flora and fauna, although full restoration may take decades.

In contrast to the field lizard, the Marmaris salamander remained perfectly still and serene, almost as if posing gracefully for the camera. Photo: Songül Karadeniz

Global warming’s ramifications for the Marmaris salamander extend well beyond the devastation of forest fires. Professor Başkale observes that this salamander depends on specific microhabitats and is compelled to seek cooler locales during bouts of extreme heat and low humidity. However, its movement is often hindered by geographical barriers. Experts warn that as the climate warms, the species is likely to shift northward, and if it cannot traverse high mountain passes to secure suitable habitat, it may face the risk of extinction. Consequently, ongoing conservation efforts are of paramount importance.

An active species action plan is in place for the salamanders, outlining annual initiatives for the period from 2024 to 2030. Officials are implementing a range of measures to safeguard the salamanders’ habitat, monitor population trends, and raise awareness to prevent the collection of these animals from the wild.

“In Fethiye, a Göcek salamander, a twin species to the Marmaris salamander, was intercepted during shipment.”

Professor Başkale explains that the conservation action plan begins with a one-year assessment of the current situation and existing conservation measures, followed by a five-year monitoring phase. “In the first year, we initiated observation and conservation studies in all known habitats of the Marmaris salamander, identifying critical areas and developing tailored plans to address emerging issues,” he says. Based on the gathered data, these studies will be expanded through coordinated efforts, including engaging with local farmers to mitigate pesticide impacts and establishing communication with provincial and district agriculture directorates.

One significant challenge is the illegal collection of salamanders for pets or scientific purposes. As part of the action plan, provincial and district gendarmerie commands have been briefed to take swift action if such activities are detected. “In the past five years, we have not encountered any major incidents, largely due to our proactive awareness and community education efforts,” notes Başkale.

The Marmaris salamander’s habitat is increasingly threatened by forest fires, extreme heat, and drought. Photo: Songül Karadeniz.

Although salamanders may be collected for scientific research, local authorities and the community have been educated on the issue. Başkale emphasizes that while local residents’ reports are valuable given the vastness of the region, they are not sufficient by themselves. “Even as we approach 2025, smuggling incidents persist. For instance, in Fethiye, a Göcek salamander –a twin species to the Marmaris salamander– was intercepted during shipment, and penalties were imposed on the sender. However, many such cases remain undetected,” he explains. He also warns of an escalating problem. “For instance, international colleagues have alerted us to private websites that trade in species prohibited for livestock or pet use. Although we file complaints against these sites, Turkey’s vast expanse often makes it impossible to intercept every instance”

The Marmaris salamander is just one among millions of species threatened by extinction, as the climate crisis, forest fires, and development-driven habitat loss all exact their toll. “There are many species in Muğla that need protection,” Başkale emphasizes, reminding us that these creatures often remain overlooked. Beyond the collaborative efforts of the Muğla Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks and the scientific community, raising public awareness among local residents and nature enthusiasts is crucial. The mellow salamander of Marmaris has persevered despite the adversities of fire, construction, and global warming. Yet, its quiet, peaceful existence beneath the stones depends not only on nature’s resilience, but also on human commitment to its conservation.

This article was published as part of a program supported by the UK Ankara Embassy’s Bilateral Cooperation Programme. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of P24. The UK Embassy cannot be held liable for the information provided in this article.