Two petitions, two academia:TR’s loneliness & universal values

What two samples of signatures tell us about the state of the academia in Turkey

31.01.2016

On 11 January 2016, an initiative from Turkey, Academics for Peace, released a petition signed by 1,128 academicians which calls on the Turkish government to end state violence and prepare negotiation conditions with the Kurdish political movement (See Appendix A).

Neither the claims nor the demands of the petition were particularly new. Human Rights Foundation of Turkey had recently released a report on civilian deaths which read “at least 22 of these people were killed while they were within the boundaries of their homes, due to opened fire or hitting by a missile or due to the direct stress effect of curfews on their health conditions;“ while Amnesty had released a letter earlier that urged Turkish Interior Ministry to respect the basic human rights of civilians under curfew, including access to food and healthcare. Members of the People’s Democracy Party (HDP), which receives the majority of votes in Kurdish towns, went on hunger strikes and literally came under fire while trying to rescue wounded civilians.

But it was the academics’ letter that turned the scales, both in terms of international support and domestic reactions.

President Erdoğan’s reaction was mostly directed at academicians. Ignoring their demands, he called them “ignorants,” “so-called intellectuals” and “lumpen circles;” and vowed that they will pay the price for “treachery.” Indeed, a criminal investigation is opened immediately on the charges of “defamation of the state and of terrorist propaganda” followed by house raids and a brief detention of 33 academicians who signed the petition. Also within the first week, many universities opened internal investigations against the signatories and, at the time of the writing of this article, 29 academics are suspended and about two hundred are being investigated. Some already left their university offices or even the cities they live in after receiving death threats —including one from a mafia leader who threatened to “spill the blood” of academics.

Despite the repression and threats, the support from both domestic and international groups poured in. Over 2,000 academics from all around the world put their signatures under the petition of Peace Academics, while others, including 30 Nobel Laureates, endorsed letters of support and called on the Turkish government “to desist from threatening academics.” Inside Turkey, many NGOs, unions, chambers and independent initiatives of various occupations declared support for academics —a full list can be found here.

But not everyone in the Turkish academia was so supportive.

Another group, Academics for Turkey, took a stand against the Peace Petition and released their own counter-petition with 2071 signatures to “voice support to the [military] operations” in the East of Turkey (See Appendix B). Theirs was endorsed by the pro-government media outlets and received no criticism from the government.

To demonstrate what these two samples of signatures tell for the Turkish academia, I archived the lists of signatories from both petitions and compared them. The results of this exercise point at significant differences in worldviews, a dichotomy that also reflects on Turkey’s map and goes well beyond the differences of opinion on the current government’s military campaign.

Two petitions, two academia

When both petitions were closed last week, Academics for Peace had 2,212 signatories.* Organisers of the second petition, however, limited their number of signees at 2,071 —to signify a millennium after 1071, The Battle of Manzikert, which is taken as a milestone in the assimilation of indigenous populations in Anatolia at the hands of Turkish tribes. However, they have listed four signatories twice, and the actual number of those who signed the second petition is 2,067.

With these two lists at hand, I created a data set of 4,279 academicians with basic variables such as gender, institutional affiliation, academic title, location; and for a smaller subset, department and research field.

gender

The gender of the signatories was unspecified on the two petitions. Therefore, I hand-coded the gender variable into female and male based on given first names. For unisex names, one half of the academics were coded female, and the other half were coded male, on a list that is not sorted by the petition type. Therefore my errors in assigning gender should be distributed evenly on both petition lists.

Out of the 4,279 academics endorsing the two petitions, 33 per cent are women — ten per cent lower than the national average in Turkish academia. When grouped by petition, 54 percent of Academics for Peace are women of various academic titles, while only 10 percent of Academics for Turkey are female overall, this ratio drops to 5 percent among associate professors and full professors.**

The higher tendency to have far right political views among men does not explain the full story here. Signatories of the Academics for Turkey petition came mostly from smaller and more traditional cities, and the distribution of academic departments may have further facilitated the gap.

department and the field of research

My initial aim for the data collection was to compare the previous academic output of academics from both groups on political science, particularly concerning the Kurdish issue. Due to time limitations, I was not able to collect this for the whole sample; therefore I randomly selected a subsample of 108 academics with at least a doctoral degree. Even though there were political scientists, sociologists and historians who published extensively about recent Turkish political history and the Kurdish issue among the Academics for Peace subsample, there were not so many who did so in the Academics for Turkey subsample, apart from one sociologist who wrote a piece on “Turkish communal identity” 20 years ago, and a few historians whose most recent period of academic interest is early Republican. Rather, many on the Academics of Turkey side were mechanical engineers, biochemists, medical doctors, and most frequently, they were researchers of Islam.

This distribution, while not allowing me to make a comparison between the two group’s opinions, gave me a good idea of the academic profile of both groups; Academics for Peace was mainly composed of social scientists, while the majority of Academics for Turkey signatories were from exact sciences — with the exception of the high number of theologists among them.

Soon I would learn that the prominence of the theology department was not just an exception.

university

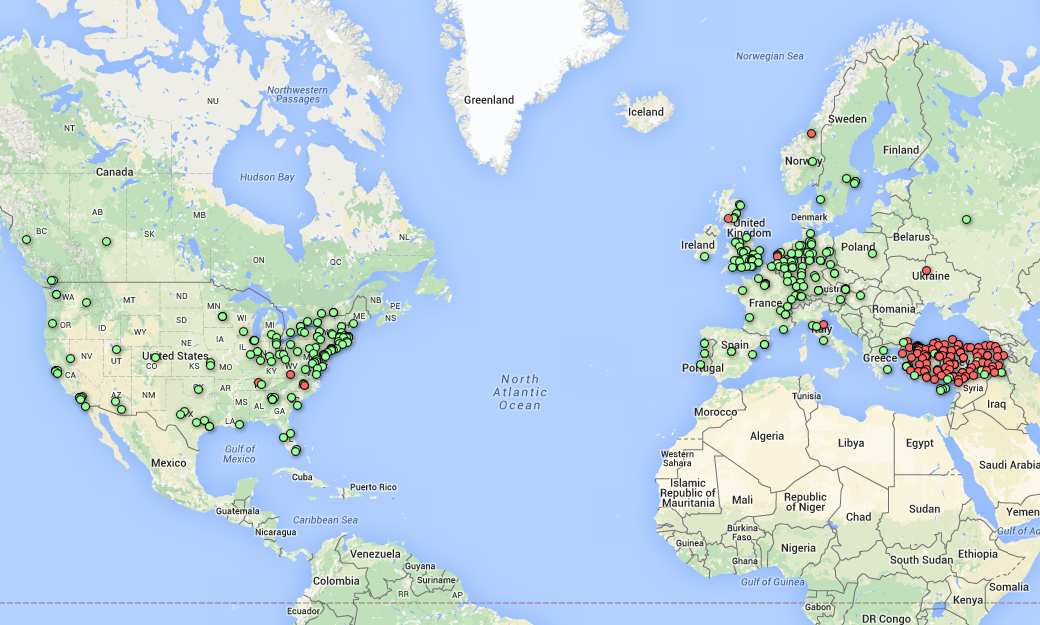

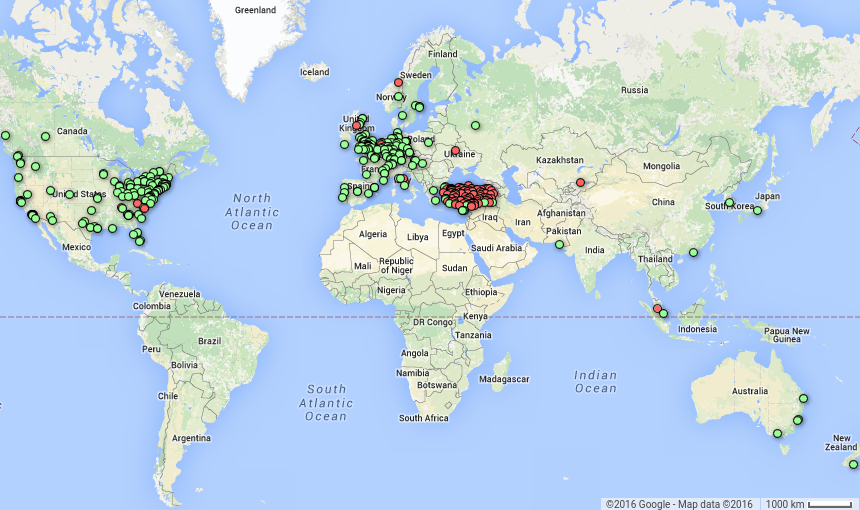

What was also remarkable in the data was that the Academics for Turkey signatures were in blocks; there were some universities in Turkey with no Peace signatories at all. Curiously, I made a simple map of universities coloured by the majority of signatories: Green for ‘’Peace,’’ Red for ‘’Turkey.’’

The Academics for Peace petition has signatories from 433 different universities, and 102 of these institutions are in Turkey. The majority of the academics are from these Turkish universities, but a more dispersed 33 percent of Turkish signatories work at institutions abroad.

In comparison, the Academics for Turkey signatures came from a much more dense list of 168 universities, only 21 of which are in other countries. Among the signatories, only 1 percent work abroad.

Measured at the university level, the two petitions are in stark contrast.

There are only a handful of Turkish universities that made it into the global top-500 rankings —see, Shanghai, Webometrics or US News: Istanbul University, Middle East Technical University (METU), Boğaziçi University, Istanbul Technical University (ITU) and Bilkent University.

When we group signatories from these five top universities in the data, 85 percent are for the Academics for Peace petition. Among the signatories from abroad, there are also Turkish academics from Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge, Princeton, Stanford, Yale and MIT.

So long to Erdoğan’s ad hominem reactions.

On the other hand, most of the universities where Academics for Turkey had the majority were founded after AKP came to power in 2003. In fact, half of the state universities (56 of them) and two-thirds of the private universities (51 of them) in Turkey today were founded under AKP’s single-party governments. Some were converted from vocational schools, some were facilitated by amendments that lift costly requirements to establish a private university. This may sound like a gigantic effort, but the expenditures in education did not double —Turkey is still at the bottom of the OECD countries in terms of education spending per GDP.

But what does the education quality have to do with the petitions?

A doctoral research [pdf, in Turkish] looked into the minutes of the parliamentary sessions and commissions where MPs discussed the budget for new universities. Since 1970s, Turkish MPs never had a concern for the lack of funds, instead all were pushing the government to build a university in their electoral district as they see universities as an opportunity to boost the local economy. By 2008, all 81 provinces finally had one of their own. Most of the new universities had administrative sciences and theology faculties which were not really serving the local needs; but instead, as the doctoral researcher wrote, the governments are politically motivated “to establish universities under the dominance of certain ideologies, and to consolidate political power via academic and administrative cadres.” The academics at these new universities are troubled by the lack of time and money for research, and admit to publishing solely for the title [pdf, in Turkish].

In this context, finding more theologists and less critical academics among the signatories from these universities makes sense. As the name suggests, Academics for Turkey is a product of recent Turkey, to serve for the political needs of current Turkey. Hence the persecution of those who signed the Peace Petition becomes a manifestation of the ‘’national’’ academia as part and parcel of the state apparatus.

geography of the minority

In similar fashion to the Turkey vs abroad and top universities vs the rest dichotomies pictured above, academics in big cities act and are treated differently than in small cities.

In the data, 90 percent of academics from three big cities (Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir) signed the Peace petition, but only 40 percent from the rest of the country. That minority were hit hardest.

To visualise this, I made an adjustment in the two-colour map: Greens are still the same, where the Academics for Peace is in majority; but the Academics for Turkey is in two steps, Reds are where all signatories are for Turkey Petition, Yellows are where there is still a Peace minority.

While the increasing political pressure on Peace Academics are turning into a nation-wide witch hunt, the first casualties were indeed from those smaller cities where the Peace Academics were the minority.

Albeit helpful in describing the problem in full frame, these numbers, charts and maps may hide the human element in this story. So let us turn to a specific incident.

Assist. Prof. Latife Akyüz was a bright sociology student accepted to METU’s Academics Training Programme in 2002. She collected data from rural Hopa town in the Blacksea Region of Turkey and wrote her 318-page English dissertation in New York and Indiana as a visiting scholar. During her studies she also took part in various research programmes for women’s participation in labour force, education of young girls, and displaced villagers due to huge dam projects. Last year, she went to Belgium as a visiting scholar to collect data on migrant women. This September, they accepted the first freshmen to the Sociology department at the newly founded Düzce University. Akyüz was the only academic who signed the Peace petition in the city. The university board immediately suspended her, police raided her house, and receiving death threats she had to flee the city and take refuge elsewhere, but due to the court’s travel ban imposed under the criminal investigation she cannot leave Turkey [in Turkish, her letter for BBC: “My life has changed in 3.5 days”].

Turkish loneliness and universal values

At this point, the readers of this article are still missing the intellectual debate between the two academia. Indeed, there is none.

On a quest to explain why Erdoğan is threatening academic freedoms, one of the Peace signatories wrote: “[In Turkey,] The value of an educated person is judged less by her inherent intellectual qualities and more by the ideological support she can offer for a political cause or the immediate material benefits her position accrues.”

Take Assoc. Prof. İbrahim Kalın, foreign policy advisor to the President, who sugarcoats Turkey’s failures in diplomacy as “precious loneliness.” As a scholar of soft power he certainly knows the practical worth of not being able to keep Turkish ambassadors in seven world capitals, including neighbours. As an advisor, he also certainly reads the foreign press which increasingly portray Erdoğan’s rule as “authoritarian,” and Turkey’s declining human rights record as “alarming.” But he is valuable as long as he can sell Turkey’s loneliness to the domestic audience.

The debate between the two academia, therefore, plays out as Erdoğan’s personal struggle for authority, but only within Turkey. Even though he manages to consolidate power and win the elections, his influence ends at Turkey’s borders as he long lost the moral high ground abroad. The call made by the Academics for Peace, however, is without borders as what is of universal value is their ideas, not their personality.

In Erdoğan’s Turkey, Academics for Peace may lose their jobs, be sent to prison or even be killed while their ‘’national’’ colleagues enjoy the benefits of a chosen elite. But whose ideas will prevail?

Notes:

I would like to thank TranslateForJustice.com for offering proofreading for this article.

* I am among the 459 doctoral candidates who signed the Academics for Peace petition.

** All infographics in this article were made online using infogr.am, all maps were created on Google Fusion Tables using Google Maps as a base.

Data set:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Ljf78XOe1q-MUB53H36VvRlXF-uxpAOShK6_9LLtow8/edit?usp=sharing

Map:

Appendix A: Original English translation of the Academicians for Peace petition released on 11 January 2016.

As academics and researchers of this country, we will not be a party to this crime!

The Turkish state has effectively condemned its citizens in Sur, Silvan, Nusaybin, Cizre, Silopi, and many other towns and neighborhoods in the Kurdish provinces to hunger through its use of curfews that have been ongoing for weeks. It has attacked these settlements with heavy weapons and equipment that would only be mobilized in wartime. As a result, the right to life, liberty, and security, and in particular the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment protected by the constitution and international conventions have been violated.

This deliberate and planned massacre is in serious violation of Turkey’s own laws and international treaties to which Turkey is a party. These actions are in serious violation of international law.

We demand the state to abandon its deliberate massacre and deportation of Kurdish and other peoples in the region. We also demand the state to lift the curfew, punish those who are responsible for human rights violations, and compensate those citizens who have experienced material and psychological damage. For this purpose we demand that independent national and international observers to be given access to the region and that they be allowed to monitor and report on the incidents.

We demand the government to prepare the conditions for negotiations and create a road map that would lead to a lasting peace which includes the demands of the Kurdish political movement. We demand inclusion of independent observers from broad sections of society in these negotiations. We also declare our willingness to volunteer as observers. We oppose suppression of any kind of the opposition.

We, as academics and researchers working on and/or in Turkey, declare that we will not be a party to this massacre by remaining silent and demand an immediate end to the violence perpetrated by the state. We will continue advocacy with political parties, the parliament, and international public opinion until our demands are met.

Appendix B: Author’s English translation of the Academicians for Turkey petition of 12 January 2016.

As academics of this country, we will stand with our state and our nation!

As everyone knows, the universities are leading institutions in societal change; they influence the society with their work in economy, technology and in social fields. Therefore, it is important that they are autonomous, independent and impartial. However, when the subject matter is the survival of the Turkish State and Turkish Nation, the academics who were raised by the opportunities provided by this country cannot be impartial. Under these circumstances, an academic can only take side with the Turkish republic which is democratic, secular, social state under the rule of law as defined in our Constitution.

Recently, a herd of so-called academics who use every chance to defame and shame Turkish Republic by libel and slander are accusing our state of torture and massacre. However, the same herd never mentions the massacred innocent babies, orphaned children, martyred and wounded police officers and soldiers by the terrorist organisation which uses rights and freedoms as an excuse; never mentions the national, religious and historical wealth destroyed by them. They keep harping on democracy and peace, but they never name the terrorist organisation who is responsible for these murders.

Unfortunately, our country has not only been subject to treacherous and despicable PKK terror, and to the bullets of this heinous organisation, but also been attacked by the so-called academics who were raised at the heart of this country for contributing its scientific and technological development. Their stand and their words are more dangerous and heinous than the bullets of the bandits in the mountains. Like every other reasonable person, we all know that the so-called peace demanded by this herd from the Turkish Republic is hiding the real purpose of their barricade politics. We believe that their petition which lacks every academic and moral sensitivities and realities have one purpose: Hindering the struggle against terrorism, and demoralise our security forces.

Consequently, as a refusal of this malicious and ignorant petition disguised as an academic one, and in a desire to express and represent the real feelings and thoughts of the Turkish Nation, we sign this petition to let everyone know that we support the operations being conducted in Sur, Silvan, Nusaybin, Cizre, Silopi and in many other places. We openly express that we completely stand with our police officers and soldiers who carefully, sincerely and bravely fight there for the peace of the nation and who left orphaned children behind.

Like those teachers and academics who went to the frontline with their students to fight against the enemy in Gallipoli, we promise and declare that we will stand against these heinous attacks with our pens and with our hearts, we will support the operations to the end, and at the same time, we will do our duty for establishing the peace as defined by the Turkish Republic.

We expect the support of academics who think like us and are in love with Turkey.